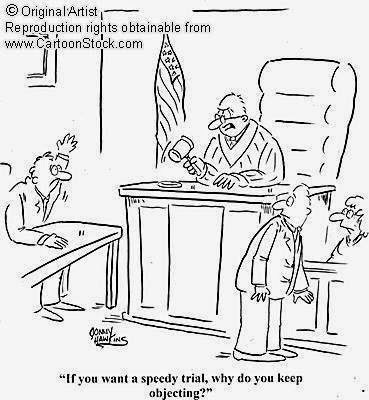

In

addition to the constitutional guarantee, various state and federal statutes

confer a more specific right to a speedy trial. The prosecution must be

"ready for trial" within six months on all felonies except murder, or the charges are dismissed by action of law

without regard to the merits of the case.

The Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees all persons accused of criminal wrong doing the right to a speedy trial. Although this right is derived from the Federal Constitution, it has been made applicable to state criminal proceedings through the U.S. Supreme Court's interpretation of the due process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Founding Fathers intended the Speedy Trial Clause to serve two purposes. First, they sought to prevent defendants from languishing in jail for an indefinite period before trial. Pretrial incarceration is a deprivation of liberty no less serious than post conviction imprisonment. In some cases, pretrial incarceration may be more serious because public scrutiny is often heightened, employment is commonly interrupted, financial resources are diminished, family relations are strained and innocent persons are forced to suffer prolonged injury to reputation.

Second, the Founding Fathers sought to ensure a defendant's right to a fair trial, The longer the commencement of trial is postponed, the more likely it is that witnesses will disappear, memories will fade, and evidence will be lost or destroyed. Of course, both the prosecution and the defense are threatened by these dangers, but only the defendant's life, liberty, and property are at stake in a criminal proceeding.

The right to a speedy trial does not apply to every stage of a criminal case. It arises only after a person has been arrested, indicted, or otherwise formally accused of a crime by the government. Before the point of formal accusation, the government is under no Sixth Amendment obligation to investigate, accuse, or prosecute a defendant within a specific amount of time.

Nor does the Speedy Trial Clause apply to post trial criminal proceedings, such as probation and parole hearings. If the government drops criminal charges during the middle of a case, the Speedy Trial Clause does not apply unless the government later refiles the charges, at which point the length of delay is measured only from the time of refiling. However, the fairness requirements of the Due Process Clause apply during each juncture of a criminal case, and an unreasonably excessive delay can be challenged under this constitutional provision even if the delay occurs before formal accusation or after conviction.

The U.S. Supreme Court has declined to draw a bright line separating permissible pretrial delays from delays that are impermissibly excessive. Instead, the Court has developed a balancing test in which the length of delay is just one factor to be considered when evaluating the merits of a speedy trial claim. The other factors to be considered by a court include the reason for the delay, the severity of prejudice suffered by the defendant from the delay, and the stage during the criminal proceedings at which the defendant asserted the right to speedy trial.

In Barker v. Wingo,

407 U.S. 514 (1972), the Supreme Court laid down a

four-part case-by-case balancing test for

determining whether the defendant's speedy trial right has been violated. The

four factors are:

·

Length of delay. A delay of a year or more from the date on which the speedy

trial right "attaches" (the date of arrest or indictment,

whichever first occurs) was termed "presumptively prejudicial," but

the Court has never explicitly ruled that any absolute time limit applies.

·

Reason for the delay. The prosecution may not excessively delay the trial for its

own advantage, but a trial may be delayed to secure the presence of an absent

witness or other practical considerations (e.g., change of venue).

·

Time and manner in which

the defendant has asserted his right. If a defendant agrees

to the delay when it works to his own benefit, he cannot later claim that he

has been unduly delayed.

·

Degree of prejudice to

the defendant which the delay has caused.

In Strunk v. United States, 412 U.S. 434 (1973), the Supreme Court ruled that if the reviewing court finds that a defendant's right to a speedy trial was violated, then the indictment must be dismissed and/or the conviction overturned. The Court held that, since the delayed trial is the state action which violates the defendant's rights, no other remedy would be appropriate. Thus, a reversal or dismissal of a criminal case on speedy trial grounds means that no further prosecution for the alleged offense can take place.

The right to a speedy trial is definitely a great way to get it done just like you guys said, but the best way i believe is taking your time and doing it right. Also up to a year for a speedy trial isn't very speedy is it now? I always use to think that a speedy trial was as soon as you committed an unforgivable crime such as murder that your sentence was carried out the same day. If only swift were an actual item in law.

ReplyDeleteKimberly Lewis Commenting:

ReplyDeleteI had the opportunity to look at the Barker v Wingo trial. I am very glad you posted this as it allowed me to look at this trial and what it meant for our further understanding, clarifying and implications of Due Process with in our legal system. I also like how this blog is clearly written and has key point information. Thank you for posting your information clearly and I like have everything gets to the point of what the blog is about.

Kimberly Again: spelling correction

ReplyDeleteI like HOW not HAVE everything gets to the point. sorry for the mistake